June 20, 2021

Yesterday, the Boone Historic Preservation Commission, the Boone Town Council, and the Junaluska Heritage Association held a joint ceremony to commemorate the unveiling of the new Town of Boone historical marker recognizing the history of the Junaluska Community.

As part of the festivities, Dr. Eric Plaag, chairperson of the Boone Historic Preservation Commission, delivered remarks contextualizing the decision to unveil the marker on Juneteenth. At the request of numerous community members who were present at the event, and with Dr. Plaag’s permission, we have reproduced those remarks below.

As we dedicate this historical marker to the Junaluska community of Boone, it’s important that we contextualize the collective decision of the Junaluska Heritage Association, the Boone Historic Preservation Commission, and the Boone Town Council to schedule this marker dedication to fall on Juneteenth, a 156-year old traditional holiday that is now—finally—recognized by our federal government for its association with the 1865 emancipation of enslaved Texans. The decision to unveil this marker today was no accident. Juneteenth festivities have long celebrated not only Black independence, but also Black culture, Black history, and Black pride. Historian Mitch Kachun has observed that modern Juneteenth celebrations also have a threefold purpose: “To celebrate, to educate, and to agitate.” I hope that our gathering here today will do all three.

First, we must understand that the emancipation that came to the enslaved people of Galveston, Texas, on June 19, 1865, was nearly 30 months late. After all, President Lincoln, under the Emancipation Proclamation that took legal effect on January 1, 1863, had already freed the enslaved people of Texas and every other state then in rebellion. When Union General Gordon Granger read General Order No. 3 aloud on June 19, 1865, he wasn’t reading a new law into effect. He was simply announcing the federal enforcement of that law in Texas. For the enslaved in many other states, though, their bondage continued. The enslaved people of Delaware, Kentucky, New Jersey, and seven of the eleven Confederate states would not see an effective end to their bondage until the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified at the end of the year. North Carolina, the second to last state to do so, did not commit to the Thirteenth Amendment until December 4, 1865.

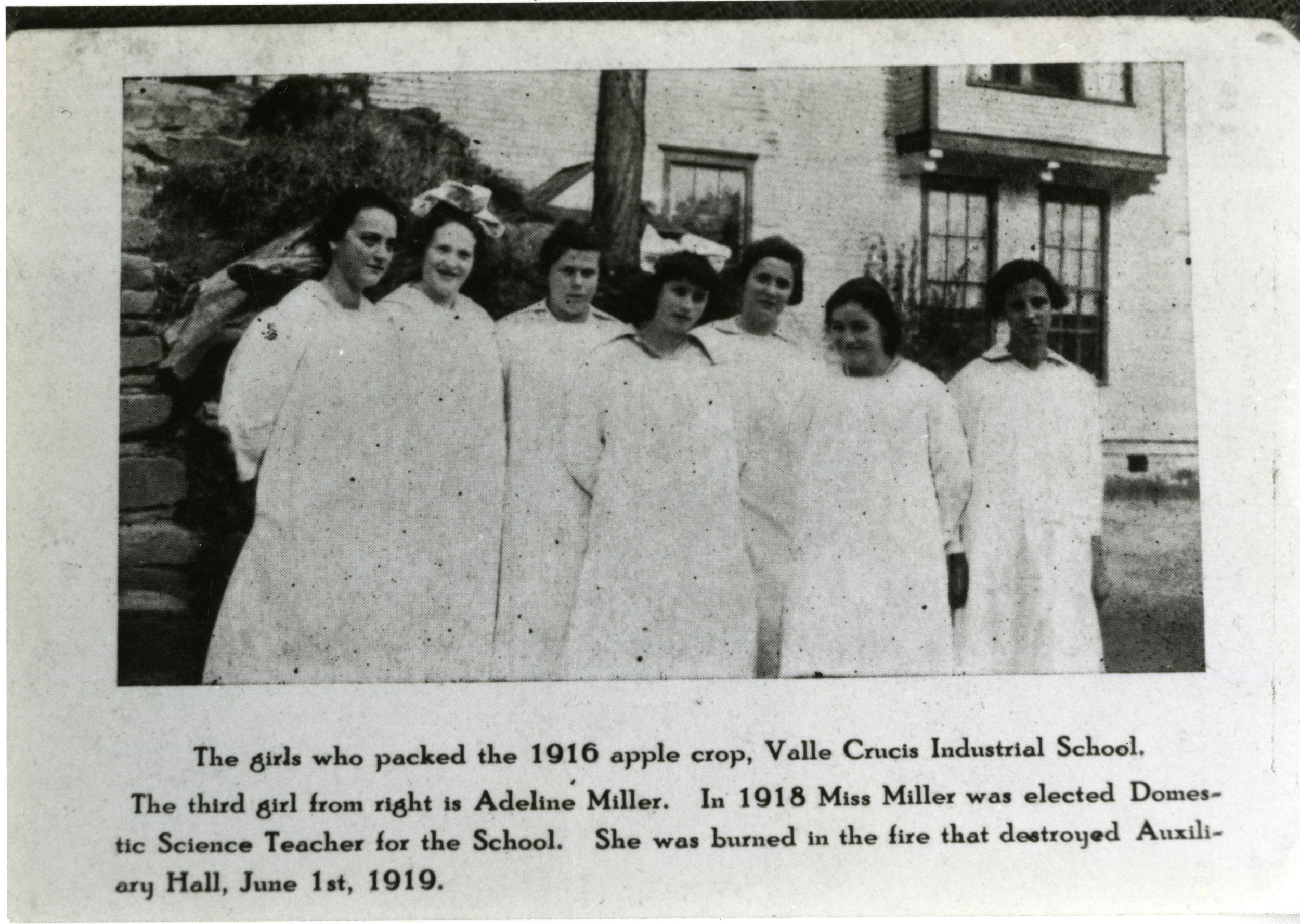

But what did freedom mean in that moment when it finally came? We do have a generalized historical sense of what freedom for Boone’s people of color meant. The 1870 Census enumerates 117 Black or mixed race individuals across 30 households within Boone’s town limits, many of whom had been enslaved by Boone’s leading families just five years earlier. Many of those freedpersons owned their own lots or sharecropped parcels on the Junaluska hillside that they had once worked in bondage, finally earning a living for themselves, rather than for those who had once enslaved them. Others took jobs as housekeepers and servants, enjoying a full day’s wages for their hard work for the first time in their lives. Some even started their own skilled trades. And by then a cohesive Black community was beginning to take shape on the Junaluska hillside, first in the vicinity of Wyn Way and upper Church Street, where the growing community built the Boone Methodist Chapel in 1898, then during the 1910s in the vicinity of North Street, Tremont Street, and lower Church Street, where Junaluska residents built the Mennonite Brethren Church that serves today as the heart of the Junaluska community.

But it would be a mistake to assume that the freedom of 1865 for the Black and mixed race residents of the Junaluska hillside meant freedom as most of us understand that word today. Freedom in 1865 was not the same as equality, and certainly not the same as equity. Freedom itself was not a great leveler. Freedom from enslavement did not, in and of itself, undo the effects of the preceding 246 years of chattel slavery on American shores. Another 156 years later, I’d argue that those effects still linger in the present-day experiences of many people of color, including those living right here in Boone. When Reconstruction ended abruptly in 1877, and whites regained control of the North Carolina legislature, a host of new ordinances—collectively known as Jim Crow laws and framed by the subterfuge of “separate but equal”—severely restricted Black freedoms and Black political power. Racial segregation—whether by law or by practice—became the standard, even here in Boone, for the next century. Junaluska’s residents were denied equal and equitable access to restaurants, train accommodations, most stores and financial services, movie theaters and entertainments, and—perhaps most importantly—the political process itself, even as those same Junaluska residents were employed in jobs that served those businesses, those services, and those local governments. Even as the US Constitution promised equal protection under the law and freedom from those kinds of race-based limitations.

Many older white folks in Boone are fond of claiming that there were “never any race problems” in Boone, and “everyone always got along.” I guess that’s an easy claim to make when the entire system is geared to validate your worldview. In reality, the residents of Junaluska endured countless indignities and injustices beyond the obvious inequities of living in a white-dominated, often segregated, and deeply prejudiced town. As a white man who has enjoyed a remarkable sense of privilege throughout my entire life, I cannot even begin to imagine the anger, frustration, and betrayal I would have felt had I been a Junaluska person of color in 1923, when a prominent, white dentist shot a Junaluska resident without cause on the streets of Boone but suffered no apparent legal consequences. Or in 1924, when a large cross was burned on a pinnacle owned by one of Boone’s white luminaries, in full view of the Junaluska community to the east. Or that same year, when the Watauga Democrat announced that town, state, and federal officials were working in concert with the local sheriff and the Ku Klux Klan to “round up” people accused of violating local laws. Or in 1925, when the Town of Boone hosted a large parade of the Klan through its streets, and the County Courthouse was host to a Klan-sponsored fiddlers convention. Or in 1926, when the Watauga Democrat announced that the former courtroom of the 1875 Watauga County Courthouse was now officially known as Ku Klux Klan Hall. Or in 1932, when a warrantless, door-to-door search of the Junaluska community ultimately resulted in the lynching of two Horton family members as they tried to flee an all-white, armed posse—an event now recognized by the Equal Justice Initiative as a racial terror lynching. Or even in 1948, when a voter drive for Black voters encouraged dozens of local people of color to vote for the first time in more than a generation but prompted our hometown newspaper to blame Blacks in advance for any “race problems” that might ensue as a result of increased Black voter participation. AND THE BEAT GOES ON. All of these injustices came even as the Junaluska community sent at least seven men to serve in World War I and at least another 23 to serve in World War II, risking their lives for American democracy and its unfulfilled promises of equality.

ENDURANCE and PERSISTENCE. Those are the words that resonate with me when I think of the Junaluska community. When the white residents of Boone closed their shops to people of color or restricted the means of access to those businesses and services for nearly 100 years, the Junaluska community members ENDURED by starting their own businesses—a barbershop, two grocery stores, a social club, repair shops, and countless home-based businesses, all in this small, hillside community. As the segregationist rules and practices finally began to relax, a bit, in the 1950s and 1960s, Junaluska residents PERSISTED, taking on more active and prominent roles in town committees, organizations, and community discussions and standing up for the best interests of their community and its residents. That endurance and persistence also required courage, an unflinching commitment to standing up for what is right and just, for what has been earned and promised, for what is required to survive.

I know that there are some folks out there who will be upset with me for calling out the ugly, racist parts of Boone’s history, but we historians have a saying: If studying history always makes you feel proud, warm, and fuzzy, you probably aren’t actually studying history. This isn’t about litigating the past; it’s about accountability. If you want to be on the right side of history, your job as a citizen of Boone is to know your community’s history—ALL of it—to acknowledge it publicly, and to do everything you can to correct and make up for its injustices. We must also work to root out the inequities that persist today because of the sins of our collective past. I will be the first to acknowledge that confronting an unspoken history of racism, especially among one’s own ancestors, is challenging and upsetting at first. But it is also enlightening and edifying. It will make you and your community better and ultimately more cohesive for having done so.

Today, Junaluska remains a close-knit, thriving community, focused on its future, but still eager to tell the story of its past. The recent oral history book about the community is evidence of that, and a must read for every single soul here today. Unlike many historical markers, THIS marker does not commemorate something that is long dead, gone, or forgotten. THIS marker educates by telling the story of how the Junaluska community was founded, how it survived, what it means for our present as a whole community, and what we as a whole community can learn from the experiences of Junaluska’s people. This marker also recognizes the importance of the Junaluska community to the Town of Boone’s history, as well as the role that many town residents and officials—including many of Boone’s “great” men and women—historically played in the oppression of Boone’s people of color.

My fervent wish is that this marker is also an agitation, prompting an acknowledgment and a commitment by all of us that there is still so much work to do locally in following Dr. King’s arc of the moral universe toward justice. It must be the first of many steps toward community reconciliation. For the moment, though, let us enjoy this day first and foremost as a celebration of the Junaluska community and a people whose endurance and persistence should be an inspiration for all of us.