Jennifer Woods, Digital Watauga Technician

On October 24, 1918, the thoughts of many Wataugans were on World War I, which had raged for four years and brought Americans into the conflict a year earlier. By October 1918, approximately 2.8 million Americans were involved in the war effort, with 358 of those being soldiers from Watauga County.[1] Families yearned for news from the front, such as that delivered to the Watauga Democrat on October 24 via a letter from Corporal Luther Bingham, who noted, “I have been with several of the Watauga boys on the battlefield, and they are all good fighters. It sure makes you feel good when you are in the thickest of the battle to look around and see one of the Watauga boys with a smile on his face, fiercely engaging the enemy.”

That October 24 issue of the Democrat carried other, much more grim news, though. One blurb spoke of the funeral of Christian Townsend, a Spanish Influenza victim from Banner Elk. Another reported on four “well-developed cases of influenza at the Methodist parsonage.” A third item indicated that Shulls Mills had seen 200 cases of influenza already with three deaths, the latest case afflicting postmaster David P. Wyke, whose “recovery is considered very doubtful” [spoiler: Wyke survived and later owned a grocery store in Boone and lived in the former Watauga County Jail]. A fourth story reported that many of the boarding students at Appalachian Training School had fled for their homes because of the influenza risk, although some had “bravely remained and waited on those who were sick.” Indeed, six weeks later, the Democrat reported that just one doctor in Watauga County had treated over 800 cases of influenza in the county, with at least another three months of cases to accumulate into the early part of 1919. For context, the entire population of Watauga County at the time was roughly 13,000.

Perhaps the most gripping story of that October 24 issue of the Democrat, though, was the news that Thomas Sims Mast had succumbed to the Spanish Flu just nine days earlier, far from home at Camp Crane in Allentown, Pennsylvania. The oldest son of Newton Lafayette Mast and Addie Horton Mast, Thomas Sims Mast was one of those WWI soldiers serving the war effort away from Watauga County. He was born June 19, 1896, and grew up in the community of Mast near the Cove Creek area. He spent the majority of his life helping on the homestead with his siblings Mammie L. Mast, Maud Annie Mast, James Brady Mast, Ernest Mast, and Mary Elizabeth Mast. Thomas attended county schools, then Mars Hill Preparatory School, and finally Wake Forest for two years before he enlisted on June 3, 1918. His first post was at Fort Thomas in Campbell, Kentucky. [2] Family correspondence indicates that he was engaged to Mary Lizzie Taylor, granddaughter of Henry Taylor of the Mast General Store, but there is no mention of a completed marriage, perhaps indicating that they decided to wait until the war was over. A copy of what appears to be their marriage license is included in Series 5 of the James B. Mast, Jr., Collection and is dated August 8, 1916.[3]

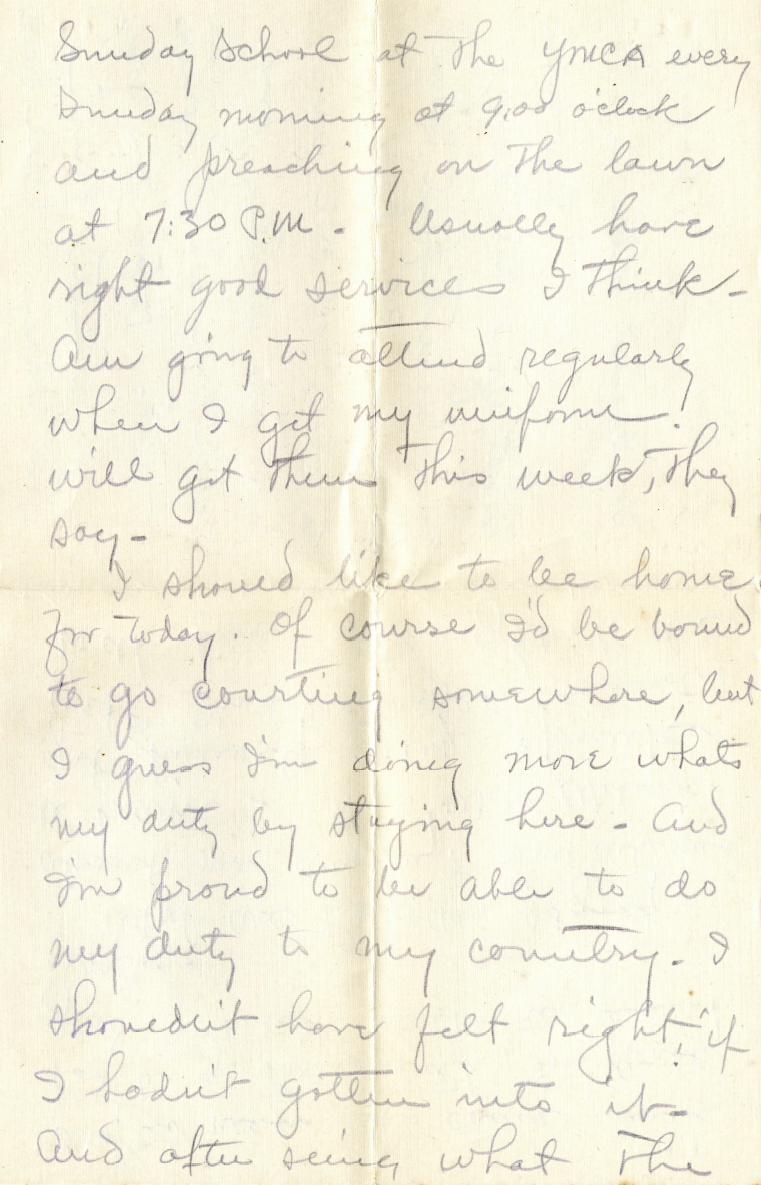

This is the second page of a letter dated June 9, 1918, written by Thomas Sims Mast to Mr. and Mrs. N. L. Mast. The letter, which appears in Series 2 of the James B. Mast, Jr., Collection, details the activities from the first week at Fort Thomas in Kentucky.

While away from Watauga, Thomas wrote to his parents several days a week. His letters from Fort Thomas mainly detail the weather and training. Six days after enlisting, he wrote that he missed home, but that he was “doing more of what’s my duty by staying here.” From Kentucky, Thomas was sent to Camp Crane in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to serve in Section 547 of the United States Army Ambulance Service. Although guard duty and food remained major focuses in his correspondence, at times Thomas slipped in other details like doing drills carrying a 50-pound pack or while wearing a gas mask. One drill required him to hike six miles with the mask on, and for another he was put in a gas-filled chamber for five minutes while wearing the mask. Both events were just small pieces that make for a much larger picture of war preparations and training. Torn between a responsibility to his family and one to his country, his letters usually included statements of resilience and acceptance: “It is hard things, after all, that are really worth something to a fellow, and make a man out of him.”

Like much of Watauga County and the rest of the country, Allentown, PA, instituted quarantines for the first wave of the flu pandemic during the spring and summer of 1918. [5] Allentown was reported to be one of the hardest hit cities, losing more than 500 people. [4] Although these quarantines are routinely referenced in Thomas’s letters, they seem more a source of annoyance than concern. The quarantine at Camp Crane is mentioned as early as July 1, 1918, with the belief that it would be lifted soon. By July 27, Mast and his fellow soldiers had selected nearby Bethlehem, PA, as their “regular hangout, as we can’t go to Allentown yet on account of the quarantine.” It is unclear if Thomas was unaware of the severity of the outbreak, if he was attempting to ease the minds of his parents, or if he was so anxious to get away from camp for a night that he disregarded the risk.

Page three of Thomas Sims Mast’s letter of July 1, 1918, clearly mentions the quarantine at Camp Crane, as well as Mast’s frustration with the limitation on his movements and his hope that it would be lifted soon. Like many soldiers and civilians, Mast found ways around the local quarantine during the summer, only to face a second wave of influenza in the fall of 1918. The letter appears in Series 2 of the James B. Mast, Jr., Collection.

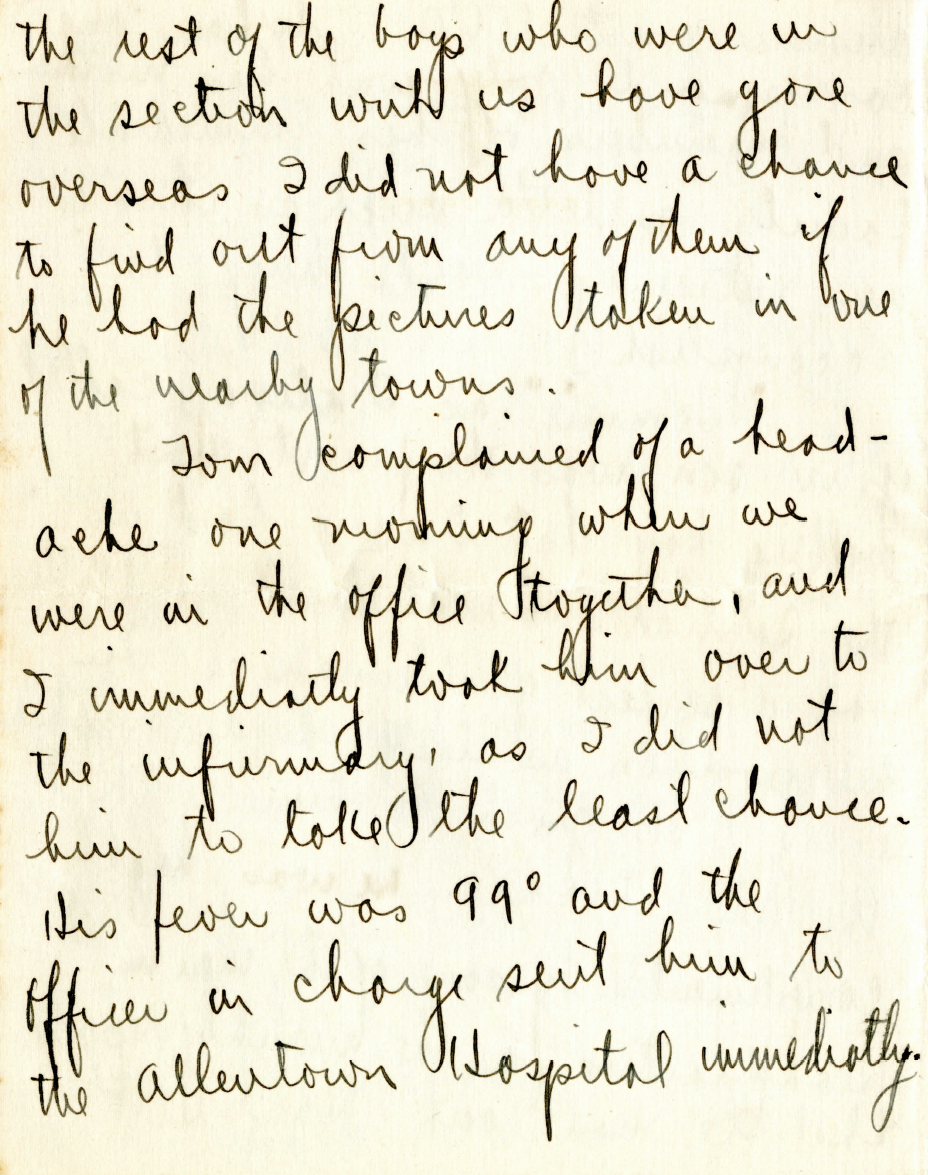

Whatever the reason, just weeks after a brief furlough to visit home, Thomas Sims Mast earned a promotion to section clerk and resumed his nights on the town, bragging in what appears to be his last letter home on September 24, “I usually go to a good show about every night I’m out, or go to a party of some kind.” Sometime in early October, Mast fell ill at Allentown with Spanish Flu, which quickly turned into pneumonia. [2] Thomas’s letters home then abruptly stopped, with letters of condolence the only explanation of his final days. Based on these descriptions, he appears to have exhibited first symptoms approximately seven days before his death. His parents were told that Thomas complained of a headache and went immediately to the infirmary, where he had a low-grade fever of 99 degrees. He was then sent to Allentown Hospital, where his fever began to climb after four days in quarantine. His father was able to make it to his bedside just before he passed on October 15, 1918. The war ended a little less than a month later without Thomas having the chance to visit home again.

This image shows page four of a letter written November 17, 1918, from Charles Boyd to Mrs. N. L. Mast. The letter remembers Thomas Sims Mast fondly while also describing his final days with Spanish Flu. The letter appears in Series 2 of the James B. Mast, Jr., Collection.

Upon receiving this box of letters, the Digital Watauga Project decided to treat items as they were, therefore housing each item as it was unveiled from the box. As such, the items in this series are not grouped by sender or date. In order to see the entire collection of these letters involving Thomas Mast, it is best to search Digital Watauga’s main site by the subject tag Thomas Sims Mast, as the letters are best read in chronological order. Also included in Series 2 are letters that detail the love story of Thomas’s parents, Newton and Addie Mast. Of particular interest is a Valentine’s Day poem lamenting the tobacco chewing habits of a “dear old bachelor.”

On a personal note, scanning and describing these letters led me down a rabbit hole of researching my family and their role in events throughout history. Our hope at the Digital Watauga Project is that this series will inspire you to revisit that old box of letters in your basement or attic and learn from your family’s past. There’s an old adage about those who forget their history being doomed to repeat it. As we hunker down now in our own homes while COVID-19 spreads across our country and the world, we hope that the tragic story of Thomas Sims Mast will serve as a good reminder of the importance of taking pandemic illnesses with the seriousness they deserve.

Stay safe, friends, and we look forward to seeing you on the other side of all of this.

[1] Thomas Sherrill, “100 years ago: The US enters The Great War,” The Watauga Democrat, April 6, 2017, https://www.wataugademocrat.com/local_history/years-ago-the-us-enters-the-great-war/article_2388d3be-c7de-58d6-9088-8cf9de1a02ce.html

[2] "North Carolina, World War I Service Cards, 1917-1919," database with images, FamilySearch, https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99X9-MDQ?cc=2568864&wc=Q6HB-44N%3A1590122304%2C1590122451 : accessed 4 December 2019), Army and Marine Corps > Mack, Robert H to Maxwell, Thomas M(arion) > image 1164 of 1463; citing The North Carolina State Archives, Raleigh.

[3] Terry L. Harmon, “Images of America Watauga County Revisited” (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2016), 86.

[4] Daniel Patrick Sheehan, “Death on parade: How the 1918-20 pandemic ravaged Philadelphia and terrorized Lehigh Valley,” The Morning Call, September 21, 2019, https://www.mcall.com/news/local/mc-nws-spanish-flu-1919-lehigh-valley-deaths-20190921-qhwt2kvjqzgpfhkesw2myb2ie4-story.html

[5] “Community-closings,” Watauga Democrat, October 10, 1918, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/8728532/community_closings/